In São Paulo, we search for Nenê, who played with Gwendolyn for Santos Futebol Club. We take a ten-minute taxi to the metro station, ride for fifteen-minutes, change lines, take another thirty-minute ride, exit at Jabaquara, have an hour-long bus ride to Ferrazópolis, meet Nenê at the station, and catch a bus to her house. “If this were Europe, you’d have gone through three different countries,” Nenê’s mom says. “Here, you are still in São Paulo.”

Her family-mother, father, eight brothers and sisters, and a dozen or so nieces and nephews-live in the two houses next door to each other. When they ask about our families and we convey that they are spread out, they ask us, puzzled, “Why?” We all feel kind of stumped.

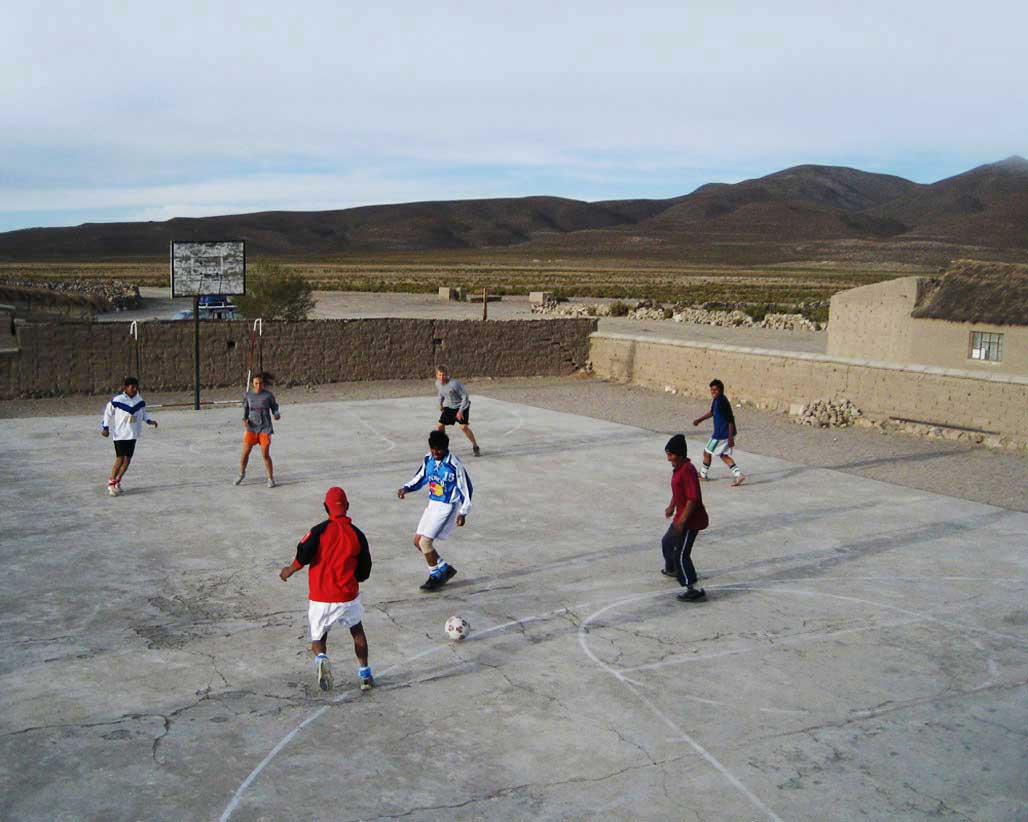

From the roof of her house, you can see down on a small enclave of São Bernardo and the concrete futebol court. Growing up, she’d come up here to see if there was a game going on. Now, 25 years-old and having quit professional soccer two years ago for a steadier job to support the family, she comes up to the roof to scout a game less often. As we watch people play, she tells us a violent personal history that makes us feel like boring, sheltered Americans.

In the morning, we follow her to work at a toy factory. Wearing hair nets and ear plugs, we film…the visuals are so interesting it’s hard to pull Ryan and Ferg away. When her shift ends, she goes out to the concrete court and checks to see who is playing before giving us the okay to pull out the cameras. The translation of the graffiti on the side of the wall: “Who is alive always shows up.” At times she still has it, flipping rainbows over the younger guys’ heads. At other times, she hangs around in the back, watching the game from a distance and looking like her mind is somewhere else. As we congregate in the kitchen after the game, her mother tells us, “I was always against it. She should live for God, not futebol. But I was at work, what could I do?”

On Sunday, we leave for Bauru, the small city Pelé grew up in. (Wikipedia will tell you otherwise…born in Minas Gerais and groomed since he was sixteen in Santos, Bauru’s often forgotten, but not to those who live in Bauru.) We meet an old man who was close with Pelé’s father. “He never did the same move twice. Even back in the days of peladas they’d carry him off the field.”

“I’ll drive you by the spot the legend used to play,” Antonio tells us. He brakes in front of a construction site for a large super market. He turns around in his seat and gestures angrily. “No respect for history.” Soon, you’ll be able to buy dishwashing detergent and cheese in Pelé’s old stomping ground. (The supermarket swears they’ll have a commemorative corner.)

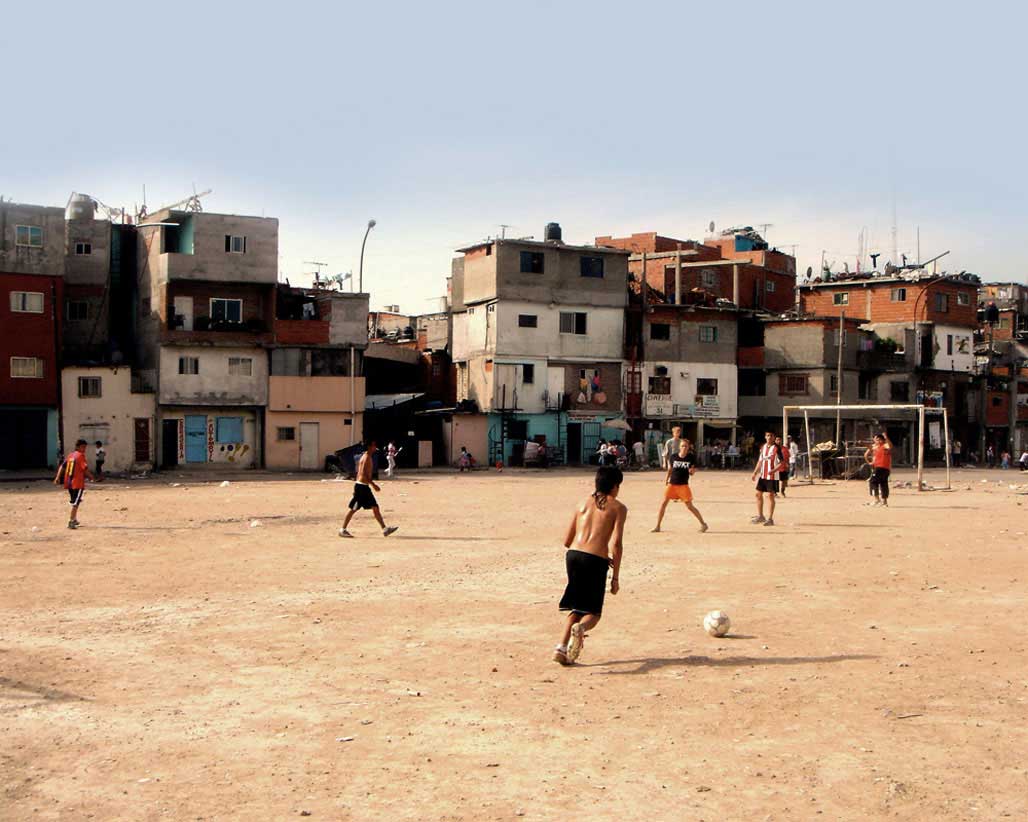

That night, we drive out to a game on the outskirts of town. “The best peladas are where the poor people play,” our friend tells us. It’s one of those schizophrenic, Florida-esque kind of skies: lightning and thunderheads to the right and sunshine to the left of the field that would look forgotten if it weren’t for the thirty-odd people playing on it. There are sporadic clumps of grass and trash dotting the orange clay. Some men wear shoes, some wear socks, some wear one sock, some wear one shoe, most play barefoot. It’s fifteen against fifteen, the type of game where you play against the other team as well as your own-everyone fighting for the ball. This game, like every game so far in Brazil, they call Luke “Alemão,” which means “German.” “Vai Alemão! Boa Alemão!” The goal is a foot-by-foot metal box and there are three guys standing in front of it. There is pretty much no chance to score. We play for two hours, nobody scores, and nobody seems too upset.

Our Brazil time is dwindling…Luke’s consoling himself with rumors that Portuguese to Spanish is an easy transition, Ferg’s studying her 501 Spanish verbs, Ryan’s saying meekly, “I got an A in Spanish seven years ago…” and Gwendolyn has just resigned herself to being the language dummy.